Tracking protection is still hard to measure

accurately, because there are many different

kinds. The Aloodo project can pick up everything,

including lesser-known vintage tools such as AVG

Crumble

and even behavior-based tools like Privacy

Badger that take

a while to get trained

and start blocking.

The biggest protection tools are the browser

built-ins. Apple Safari has had Intelligent Tracking

Prevention, and Mozilla Firefox is testing Enhanced

Tracking Protection. We have added a quick test that

should cover both of these. Now there is an

onBlocked callback to take action when we can detect

right away that a user has this form of protection

because a third-party cookie won't persist.

Code: Add "cookie blocked" message · Aloodo/ad.aloodo.com@1915f0b

According to conventional adtech and martech, exactly 0% of users are blocking tracking by conventional adtech and martech.

You can look at ad blocking rates by market to get an idea of how many "invisible" users there are, but the "headline rate" for ad blocking has two problems.

The ad blocking rate mixes up users of three kinds of software: tracking protection tools that block only third-party tracking (such as Privacy Badger), pure ad blockers that block both third-party trackers and ads (such as uBlock Origin) and ad blockers that run paid whitelisting schemes (such as Adblock Plus).

Ad blocking and tracking protection percentages are vastly different from site to site. Some sites serve a community of practice whose members install a lot of privacy tools. Some sites don't.

For example, several sites that cover web development and devops are getting tracking protection rates around 30%. One site is around 40%. But if you look at the average tracking protection rate for a country, you don't see how much of a brand's audience is less trackable. (You can't walk across a river that is an average of two feet deep.) What does this mean for brands?

If you're not reaching people, you're not reaching them. Most of today's web advertising is invisible to users of some privacy tools and ad blockers.

Higher blocking rates don't necessarily mean you get billed less for ad impressions. They can mean that more of the impressions you do get billed for are bots.

Data-driven marketing decisions get you the wrong answers if real customers get consistently missed.

What can brands do? The first step is to figure out if a brand has the kind of protected customers who make it necessary to do something. If all the customers are neatly trackable, that brand probably has higher priorities. (protip: brand safety)

If you run the test and the customers are better protected from tracking than the average, that's where the opportunity comes in.

While the competition wastes their budget on reaching the wrong people, or bots, they're not getting to the tracking-protected audience. Knowing if you have tracking-protected customers is the first step in building creative ways to reach them.

Next steps: JavaScript instructions, or contact us using the form below.

In today's marketing news, Amazon is introducing a new ad retargeting service.

The tool lets merchants selling on Amazon’s online marketplace to purchase spots that will follow shoppers around the web to lure the consumers back to Amazon to buy.

So far, pretty straightforward. But the big question for brand advertisers is: how does this new feature interact with Amazon's notorious counterfeit products problem?

Amazon said it can help merchants target shoppers who have viewed their products or similar ones, according to an invitation to try the new tool that was viewed by Bloomberg News.

This clearly presents a problem for legit brands.

Brand offers a product on Amazon.

Some deceptive seller offers a counterfeit version.

Shopper visits a page for the legit product.

Deceptive seller out-bids the legit brand for retargeted ad impressions (which they can easily afford to do, because they're shipping a crappy product)

Shopper returns to Amazon and buys the counterfeit product.

Amazon and the deceptive seller win; the original brand and the customer lose.

For brands using a reputation-based

strategy, conventional data-driven marketing

tactics can only do so much to help here.

Today's adtech and martech platforms are optimized for

game-changing

interactions that tie marketers to third-party data

sources, not for brand building. Targeted advertising

tends to give an unfair advantage to deceptive

sellers,

and the tools available to legit brands are less

well known.

Does this mean that ad agencies that create value by helping to build brands now have an opportunity (or even a responsibility) to include tracking protection for customers as part of an integrated strategy? I know that the upcoming Nudgestock is not just a marketing conference, but I'll be speaking there and would be happy to discuss this kind of thing if it comes up.

Doc Searls writes, at Linux Journal, about the site's re-launch plans. Linux Journal is moving to an all-subscription model.

We believe the only cure is code that gives publishers ways to do exactly what readers want, which is not to bare their necks to adtech's fangs every time they visit a website.

We're doing that by reversing the way terms of use work. Instead of readers always agreeing to publishers' terms, publishers will agree to readers' terms.

The Linux audience tends to be early adopters of privacy tools, which means that brands need new kinds of metrics. When you're trying to reach niche early adopters such as the open source and devops audiences that Linux Journal serves, conventional adtech and martech aren't enough.

The readers of Linux Journal have

overwhelmingly rejected web advertising. This

is strange, because as a former editor there

back when they had a print magazine, I recall

that readers didn't have much of a problem with

the print ads. We got the usual bragging that

ads don't work on me,

but print ads don't

work the way that most people think they work

anyway.

The Linux Journal ads got crappy when they went web-only. Instead of a sustainable revenue source, the ad game became a race to the bottom. And LJ almost lost that game.

The good news is that the game is changing because of hard work happening on the browser side. Every time a user turns on a privacy feature such as Firefox Tracking Protection, or installs a protection tool such as Better by ind.ie or EFF Privacy Badger, a little bit of problematic ad inventory goes away. When tracking protection tools keep ad money out of the nasty corners of the internet, legit sites can win. Here's how Aloodo plans to help LJ, and is available to help other sites too.

Measure the tracking-protected audience. Tracking protection is a powerful sign of a human audience. A legit site can report a tracking protection percentage for its audience, and any adtech intermediary who claims to offer advertisers the same audience, but delivers a suspiciously low tracking protection number, is clearly pushing a mismatched or bot-heavy audience and is going to have a harder time getting away with it. Showing prospective advertisers your tracking protection data lets you reveal the tarnish on the adtech "Holy Grail"—the promise of high-value eyeballs on crappy sites.

Tracking protection is hard to measure accurately, because there are many different kinds. What works for detecting AVG Crumble might not work to detect Privacy Badger. But now anyone with basic web metrics and JavaScript skills can do the measurement with the Aloodo un-tracking pixel and scripts.

Use data to sell brands on Flight to Quality. Real, high-quality sites have branding advantages over generic eyeball-buying, and adfraud is becoming a mainstream concern. The complex adtech that tracking protection protects against is also the place where fraud hides. (Adtech also tends to drag brands into Internet poo-flinging contests by attaching them to controversial sites, but that's another story.)

Higher-reputation publishers need more and better data to take to numbers-craving CMOs. Much of that data will have to come from the tracking-protected audience. When quality sites share tracking protection data with advertisers, that helps expose the adfraud that intermediaries have no incentive to track down.

We look forward to working with Linux Journal and the LJ readers.

Aaron Harris writes,

As more things in our lives become hackable, we’ll need more help protecting ourselves from those things. Existing companies that focus on homeowner’s insurance are unlikely to understand these issues well enough to create great products.

If a user visits an insurance site for a personal

cyber insurance

quote, will the number be

higher or lower of the user is running Privacy

Badger? How about Apple Safari with Intelligent

Tracking Prevention?

If you need to check a user's browser to make sure they're protected from third-party tracking and all its negative security externalities, we have a tool for that.

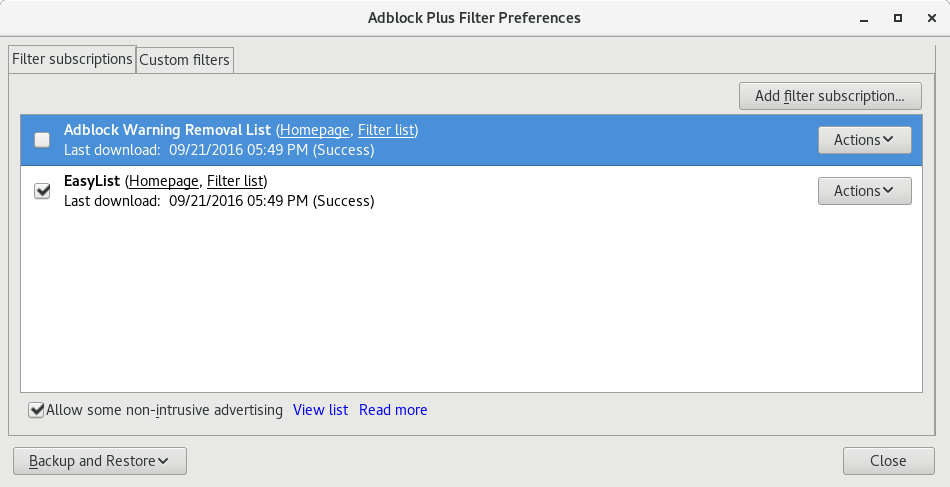

Some sites recommend Adblock Plus (or just "an ad blocker," for which Adblock Plus is often the first search result) as a privacy or security tool. But Adblock Plus uses deceptive "dark patterns" to avoid offering real privacy or security to users.

Please do not recommend either Adblock Plus or "an ad blocker" to users who are concerned about web privacy or security.

Adblock Plus runs a paid whitelisting program called "Acceptable Ads". The "Acceptable" criteria include no rules against common user privacy and security concerns, such as malvertising and PII misuse. And configuring Adblock Plus to actually provide tracking protection is complicated.

Go to "Filter Preferences" in the ABP menu.

Click "Add filter subscription"

No privacy lists appear on the main drop-down. You will have to hunt for them behind "Add a different subscription".

Scroll down and eventually find the "EasyPrivacy" entry from a long list.

Click "Add subscription".

So far, it's time-consuming and deliberately complicated, but not deceptive. (Keep this in mind when Adblock Plus proponents talk about how users are mad about annoying ads but don't mind tracking. If users don't mind tracking, why did Adblock Plus make it so hard to make the choice?)

Turning on a privacy list is enough of a maze to discourage users, but not deceptive deceptive. That's found in another place.

Now for the deceptive part.

Even after you go through the above five-step (!) process to find and turn on "EasyPrivacy", you're still not protected. This is not clear unless you read the fine print. The "Acceptable Ads" paid whitelisting program actually overrides your explicit EasyPrivacy choice, to allow tracking by Google, Criteo, and other companies.

In order to make your tracking protection choice take effect, you also have to turn off "Acceptable Ads" using a different option, which is labeled "Allow some non-intrusive advertising."

To really block trackers, un-check a box with a label that says nothing about trackers at all.

The checkbox is not even labeled "Acceptable Ads," maybe just in case a user has heard of "Acceptable Ads" and knows about the controversial paid whitelisting program.

What to do instead

The good news is that alternatives are available.

Instead of recommending "an ad blocker," link to a list of legit tracking protection tools, or make your own list of tools that work well with your site. It's easy to use a JavaScript browser detector like bowser to recommend an appropriate one for the user.

If you maintain a directory of web software, please do not list Adblock Plus in a privacy or security category.

Geoffrey A. Fowler, at the Wall Street Journal, shares some good first steps for users to to protect themselves from online tracking, in Don’t Expose Yourself: A Guide to Online Privacy. Read the whole thing, even if you have tracking protection. Lots of up-to-date recommendations on current tools and opt-out options.

But the personal side of web tracking protection is only part of the story. Walt Mossberg ran into the business side of the tracking problem while at The Verge:

About a week after our launch, I was seated at a dinner next to a major advertising executive. He complimented me on our new site’s quality and on that of a predecessor site we had created and run, AllThingsD.com. I asked him if that meant he’d be placing ads on our fledgling site. He said yes, he’d do that for a little while. And then, after the cookies he placed on Recode helped him to track our desirable audience around the web, his agency would begin removing the ads and placing them on cheaper sites our readers also happened to visit. In other words, our quality journalism was, to him, nothing more than a lead generator for target-rich readers, and would ultimately benefit sites that might care less about quality.

High-reputation sites such as the Wall Street Journal can't enforce ad standards when an original content site is in direct competition with bottom-feeder and fraud sites that claim to reach the same audience. But when users install privacy tools such as Better by ind.ie and EFF Privacy Badger, a lot of problematic ad inventory goes away. Crap sites can only make money from users who are vulnerable to third-party tracking. When tracking protection tools keep ad money from flowing to crappy and fraud sites, then the Wall Street Journal wins.

Real, high-reputation sites have branding advantages over generic eyeball-buying. and users are concerned and confused about web ads. That's an opportunity for a high-reputation publisher to get users safely protected from tracking, and not caught up in publisher-hostile schemes such as paid whitelisting, ad injection, and fake ad blockers. (The New York Times gets it too: Free Tools to Keep Those Creepy Online Ads From Watching You)

More info: What The Verge can do to help save web advertising

Next steps: Aloodo for publishers

Europe is getting new privacy regulations that will limit surveillance marketing.

I see their point. Instead of making people navigate the fine print of privacy policies and click through broken opt-out systems. the EU is trying to save everyone some time and risk.

Meanwhile, California, like the rest of the USA, has basically zero privacy. But we do have great burritos here, so we've got that going for us anyway.

Some surveillance marketing proponents say that if Europe rolls out GDPR, then there goes all the creative stuff on the Internet. (which is roughly what the DRM proponents said about DRM, but Hugo-award-winning author Charles Stross already explained that one.)

Personally, I agree with Doc Searls that the role of privacy violation in ad-supported Internet services is way overrated. Most of the value is in ad context (what site the ad is on) and search (which does have some customization based on who you are, but mostly works based on what you search for.) Targeting just provokes blocking and makes ads less valuable. So GDPR won't break the Internet, or even ad-supported sites. I'm confident enough in this that I will back it up with an offer.

If the surveillance marketers are right, then Europeans would be deprived of some neato Internet services that we, here in California, are allowed to have. So, demonstrate for me an Internet service that is...

mentioned in a news story as creative or innovative

not offered in Europe, and the company behind it has stated that they won't offer it in Europe because GDPR.

...and I'll buy you a California burrito and link to the service from here and on Twitter. First five demos get a burrito and link.

If I'm right, then Europeans will get better advertising, a safer Internet, less fraud, stronger brands, and I'll get to eat the burritos myself.

Web advertising is a dangerous mess. But why keep thinking about it as a "let's have a meeting about it" problem? It's more of a "what can I fix now and make serious money doing it" problem. Read on for a link to some JavaScript that a brand advertiser (or publication, but we covered that before) can start using today.

The opportunity comes from the fact that low-reputation and high-reputation brands need fundamentally different qualities from an advertising medium.

Low-reputation brands need to send ads only to people likely to respond.

High-reputation brands need to send a costly, hard-to-repudiate signal to an large audience.

When an ad medium is targetable, sellers lose the ability to signal. When an ad could have been targeted to a small group, you can see that the advertiser isn't spending as much to reach you.

Most people are pretty good behavioral economists. They may not know anything about how the products they buy work, but they know how to read the advertising signals.

Signaling failure is obscured by all the other problems that web advertising has. You're lucky if your brand's ad ends up being shown to an adfraud bot, because if that ad gets through to a real user, it's probably attached to a beheading video or conspiracy theories or malware or something. What a shitshow.

People are still nerding out over new technologies without fixing the obvious problems, never mind the deep problem of signaling failure.

Work together? Why not?

Fortunately, web advertising is not a problem where "the industry" needs to "work together". Mark Glaser, on the DCN site, does an excellent job of identifying the problems. But he writes,

If the demand for money and efficiency is eroding the integrity of content—not to mention that of brands and platforms—everyone involved must collaborate to gain that trust back.

In the IT business, this kind of call for coordinated action is what executives from legacy companies say while they're getting ready for an expensive conference with a golf tournament. And they say it right about the time that an independent programmer in a basement somewhere is writing the code to eat their lunch. When a whole industry is wrong about something, that doesn't mean you have a big boring assignment to persuade everyone in the industry. It means you have an opportunity to make mad cash by being right. A good agency working independently can solve the web advertising problem for one brand, just as a good publication working independently can solve the web advertising problem for its own audience.

If your idea of a solution to the web advertising problem involves meetings about how everybody has to solve the problem or nobody can, then I've got nothing for you. Go look at cat GIFs or something.

Still with me? Good.

The more that a user gets protected from tracking and targeting, the more signalful the web becomes as an ad medium from that user's point of view. This can work one user at a time. No coordination required. It's a matter of informing and nudging users to take precautions and become less trackable. Please grab the code (it's open source) and try it out.

What kinds of brand advertisers will be good early adopters for tracking protection strategies?

Does the brand have noisy, low-reputation competitors?

Some high-reputation categories are great fits for tracking protection because there are so many rip-offs using targeted web ads.

Insurance

Financial services

Health care

Does the brand depend on reputation earned over long-term use?

Look for goods that are difficult to evaluate at point of purchase and where an experience with a deceptive seller can be costly.

High-signal advertising is a way to take a position on future customer satisfaction and what kind of word of mouth that the brand is betting it will earn.

Tools

Cookware

Is the email list an (expletive deleted) gold mine?

This is an easy one. If you already have the customers reliably opening your email, or participating in some other medium such as a customer web board, you've got great data and nothing to lose by helping to deny their info to the competition. Play defense.

Does the brand already have a tracking-protected customer base?

Some product categories already appeal to Internet "privacy nerds" who are hard to reach by conventional web ads. Worse, conventional marketing tech is giving you really bad numbers when enough of the customer base is "invisible". Tracking protection strategy is essential here, just to keep from getting wrong answers. Don't do a big new product launch based on what bots want.

Next steps

If you answered "yes" to one or more of these, the first step is to collect some data on tracking protection adoption among the brand's customers and prospects. A high-traffic support or service page is a good place to install tracking protection measurement to get a baseline measurement on how well-protected the audience is. From there, it's a creative marketing project to customize a tracking protection campaign—something new and different to offer to a brand stuck in the online advertising mess.

Please let me know if you have any questions.

Bonus link: Brian O'Kelley, Data is fallout, not oil

A new digital ad medium is making its way up the upward slope of the Peak Advertising curve.

Aldo Agostinelli of Sky Italia writes,

In the age of the IoT, web-connected devices are the new smart tools that will give advertisers unprecedented access to their users’ daily lives. But there is more to it: the IoT could also help advertisers deliver timely messages and persistently reach consumers.

This is how all targeted ad media, from direct mail to junk fax to mobile banners, get their start. Some Marketing person comes up with the idea of using some new technology to better target some users but not others.

Pass the popcorn. We've seen this show before.

Now it's time for a flood of videos from agencies about how well the new medium works, surveys where marketers say they're going to put budget into it, a bunch of VC funding for firms that do it, and before you know it, the new medium is something that marketers don't want to be caught not doing. The whole shitty carnival of "let's build a new targeted ad medium" is in town. Or in this case, on your toaster.

For a little while anyway.

Marketers know that you have to enjoy the new targeted ad medium while you can. Any new targeted ad medium always peaks, and then declines—right about the time users figure it out.

It's not that the technology is bad. Many new targeted ad media do provide technical advantages in more accurately matching ads to users. But somehow targeted ad media always go through a boom and bust cycle, unlike mass media advertising, where print and broadcast ads tend to hold their value.

Peak Advertising in targeted ad media keeps happening, because, as Agostinelli writes,

The IoT has many benefits for advertising: not only can a message related to a product reach a specific and clearly identified target audience, but the message can be designed based on data which makes it more personal and, therefore, more efficient.

Read that again. That's where every targeted ad medium

breaks down. Efficient

is why users bail.

They start voting to ban junk faxes. They start

running spam filters and ad blockers. And yes, they

will, somehow, figure out how to kick the targeted

ads off their toasters.

Meanwhile, users continue to accept magazine ads and at least tolerate the TV commercials. It's the targeted ad media, the ones that sound the coolest and most efficient, that get ignored, blocked, and regulated.

Let me share with you a sentence that's an obvious, even stupid, platitude for regular people, but a strange and terrible secret for digital advertisers. Ready?

There's no such thing as a free lunch.

Advertising, done in a sustainable way, is an exchange of value between the advertiser and the audience. The audience gives up some attention as the ad interrupts an ad-supported resource such as a news story or cultural work. In exchange, the advertiser offers economic signal, a hard-to-fake message about the advertiser's intentions in the market.

When a targeted ad medium helps advertisers try to get a free lunch by cutting back on the signal—by making it hard for users to estimate the amount spent to place the ad—the user no longer has an incentive to "pay" for the ad with his or her attention. The Peak Advertising curve is the result of users figuring out the targeting.

User tracking and targeting projects, built at tremendous expense, make an ad medium less valuable, not more. This is hard for computer nerds to understand. "What do you mean my program makes things worse? But it was so hard to write!"

No ad medium entirely goes away. When the IoT advertising hype is over, crappy toaster ads will remain, spreading security problems and brand-unsafe ad placements just like crappy web ads do today. The trick for brands is to sit back and enjoy the show, not get ripped off.

Walt Mossberg, at The Verge, points out that lousy ads are ruining the online experience.

No doubt about that. Web ads are crap.

Just try reading the same newspaper story in print and online. In print it's next to a professionally-shot photo in a kitchen remodeling ad. On the web it's next to YOU WILL DIE FROM LIVER FUNGUS UNLESS YOU CLICK ON THIS INFECTED LIVER NOW, done in MS Paint.

And it seems to be getting worse, not better. (Not surprisingly, ad blocking keeps going up.) The ads that provoke blocking and mockery are the same ones that get clicks. Everyone agrees that "we" need to get rid of "bad" ads. But naturally, "we" is defined as "you" and "bad" is "not the ads that work for me."

Print ads stay tolerable because in print, publishers have the market power to enforce standards. On the web, not so much. Mossberg again (read the whole thing):

About a week after our launch, I was seated at a dinner next to a major advertising executive. He complimented me on our new site’s quality and on that of a predecessor site we had created and run, AllThingsD.com. I asked him if that meant he’d be placing ads on our fledgling site. He said yes, he’d do that for a little while. And then, after the cookies he placed on Recode helped him to track our desirable audience around the web, his agency would begin removing the ads and placing them on cheaper sites our readers also happened to visit. In other words, our quality journalism was, to him, nothing more than a lead generator for target-rich readers, and would ultimately benefit sites that might care less about quality.

Publishers can't enforce ad standards when an original content site is in direct competition with bottom-feeder and fraud sites that claim to reach the same audience. As Aram Zucker-Scharff mentions in an interview on the Poynter Institute site, the number of third-party trackers on a site grows as new advertising deals bring new trackers along with them. Those trackers leak audience data into the dark corners of the Lumascape until the same data re-emerges, attached to a low-value or fraudulent site that can claim to reach the same audience as the original publisher. Deceptive and extremist sites are part of a larger problem. They're just especially good at playing the same adtech game that all low-value sites do.

So how to turn web advertising from a race to the bottom into a sustainable revenue source, like print or TV ads? How can the web work better for high-reputation brands that depend on costly signaling?

The good news for cash-crunched news sites is that the hard work of web-ad-saving software development must happen, and is happening, on the browser side. Every time a user turns on a protection tool such as Better by ind.ie, EFF Privacy Badger, or the experimental Firefox Tracking Protection, a little bit of problematic ad inventory goes away. Crap sites can only make money from users who are vulnerable to third-party tracking. When tracking protection tools keep ad money out of the nasty corners of the internet, legit sites can win.

For example, if a chain restaurant wants to advertise to people in a town, today they have a choice: support local news, or pay intermediaries who follow local users to low-value sites. When the users get protected from tracking, opportunities to reach them by tracking tend to go away, and market power returns to the local news site.

The Verge and other legit sites are a key part of the solution. The problems of web advertising have grown over years, and won't go away all at once. Sites will have to fix it in a data-driven, incremental way. Fortunately, we're getting the data to make it happen.

Measure the tracking-protected audience. Tracking protection is a powerful sign of a human audience. A legit site can report a tracking protection percentage for its audience, and any adtech intermediary who claims to offer advertisers the same audience, but delivers a suspiciously low tracking protection number, is clearly pushing a mismatched or bot-heavy audience and is going to have a harder time getting away with it. Showing prospective advertisers your tracking protection data lets you reveal the tarnish on the adtech "Holy Grail"—the promise of high-value eyeballs on crappy sites.

Tracking protection is hard to measure accurately, because there are many different kinds. What works for detecting AVG Crumble might not work to detect Privacy Badger. But now anyone with basic web metrics and JavaScript skills can do the measurement with the Aloodo un-tracking pixel and scripts.

Use data to sell brands on Flight to Quality. Real, high-quality sites have branding advantages over generic eyeball-buying, and adfraud is becoming a mainstream concern. The complex adtech that tracking protection protects against is also the place where fraud hides. (Adtech also tends to drag brands into Internet poo-flinging contests by attaching them to controversial sites, but that's another story.)

Higher-reputation publishers need more and better data to take to numbers-craving CMOs. Much of that data will have to come from the tracking-protected audience. When quality sites share tracking protection data with advertisers, that helps expose the adfraud that intermediaries have no incentive to track down.

Use service journalism. Users are already concerned and confused about web ads. That's an opportunity for The Verge. The more that someone learns about how web advertising works, the more that he or she is motivated to get protected. A high-reputation publisher can win by getting users safely protected from tracking, and not caught up in publisher-hostile schemes such as paid whitelisting, ad injection, and fake ad blockers.

Here is a great start, on the New York Times site. Read the whole thing:

Free Tools to Keep Those Creepy Online Ads From Watching You by BRIAN X. CHEN and NATASHA SINGER

Some ways to both help users and work in the interests of a quality site include:

review and recommend tracking protection tools, as a new part of everyone's basic security toolkit

Detect users who are vulnerable to third-party tracking, and recommend your site's top-rated tool for their platform.

Offer bonus content to tracking-protected users.

Can't hurt to expose the protection racket behind AdBlock Plus, either.

Beware nerds who claim to fix everything (including me). High-reputation sites are still skeptical about alternate web business models, which is a good move. Better to put the resources into doing some careful adblocker workarounds, advocating responsible tracking protection, and working on magazine-style ads where the four-currency price of accepting the ad is lower than the four-currency price of blocking it.

Upgrading web advertising to a high-signal medium

Why do people watch and share Super Bowl commercials while web ad blocking continues to trend up?

The problem is that the story of web advertising has been one of frantically throwing technology at the lowest-value parts of the ad business while reducing the power of web ads to get a piece of the high-value parts. People who live in market economies are pretty good applied behavioral economists. They'll pay attention to ads that pay their way, with signal, while avoiding cold calls and ads that, through tracking and targeting, work like a cold call and fail to carry signal.

The challenge facing sellers of some genuine product—be it true late-night love or a Tiffany necklace on eBay — and the buyers in search of them is to prove that they’re not just full of empty words. This is where Super Bowl ads come in. Airtime during the game is, of course, fantastically expensive. So why do companies bother buying it? For the same reason that gang members get face tattoos: to prove that they’re in it for the long haul.

The researchers found that highly targeted and personalized ads may not translate to higher profits for companies because consumers find those ads less persuasive.

Privacy projects such as Better by ind.ie, EFF Privacy Badger, and Firefox Tracking Protection aren't just ways to implement the kind of personal data protection that users want. Those projects can also work in the interests of high-reputation sites, by making signaling work better. Sites like The Verge can help, by helping users squeeze out the signal-destroying tracking and targeting, and helping web ads become a signal-carrying medium.

Next steps: Aloodo HOWTO

A lot of the responses to Methbot have been along

the lines of hey, look, a squirrel!

So here are

a few of the non-squirrel things to think about.

Methbot does two interesting things. Adtech is fixing one of them.

White Ops published some good info on two Methbot capabilities.

Spoof data center IP addresses as residential

Work around anti-fraud software

Almost all of the news about Methbot is focused on the first one. But look at the original White Ops report (PDF) and skip to page 24.

The White Ops security research team found traces of analysis code where Methbot developers dissected the logic of the most widely adopted fraud detection vendors on the web. It’s apparent that they spent some time reverse-engineering these capabilities, manually running portions of measurement code inside legitimate browsers to learn what its output looks like, and then porting the logic to spoof those values in Methbot execution context.

And page 25.

In addition to code specifically designed to defeat viewability measurements used by specific vendors, White Ops found routines for spoofing industry-standard measurements. In particular, flash VPAID events are expected and handled.

Methbot impressions are more viewable

than

human impressions. Methbot is a more skillful

Web user than the average CMO. Augustine Fou

writes,

To put it bluntly, bad guys don't even care to find out the actual secret sauce of the various fraud detection companies because they have already A/B tested their bots and know for sure they get by various detection platforms. In fact they openly sell "fraud vendor compliant" traffic on a CPM/CPC basis.

When you pay for anti-fraud technology,

you're just paying for the software

testing that fraud hackers are using to build

better bots. White Ops CEO Michael Tiffany told

AdExchanger,

The ultimate source of truth about where an

advertising opportunity is happening is in the

browser—but if you carefully rig the browser

to lie about that, there is almost no defense.

There is one defense. It has two parts, tracking

protection

and flight to quality,

and

we'll hear more about it in 2017.

Methbot didn't cost advertisers any money.

Advertisers already know about adfraud in general. Methbot was just one ambitious example. Other fraud rings are still doing what they do. If you got an Internet of Things device for Christmas, it might already be running a bot. Methbot's IP addresses are no more, but the anti-anti-fraud code lives on.

When enough players in a market know about a problem, it's priced in. And adfraud has been priced in to the online ad market for a long time. (This is why the recommendations at Shortin' Adtech are bogus. Advertisers and investors can flee web advertising, but have no incentive to, because publishers pay for fraud. Publishers can't flee, because online is displacing print, but they have every incentive to if they could. An important reason for the "print dollars to digital dimes" problem is that everyone is used to paying the fraud-adjusted price.)

For every dollar that adfraud costs advertisers, they save a dollar or more in lower costs for legit ads. For every dollar that adfraud takes out of the game, publishers lose more. This is pretty basic economics, and explains why advertisers are willing to talk but not take action on the adfraud problem.

Data-driven

can turn into bot-driven.

Advertisers do pay for adfraud, but not in money.

When you're running a data-driven organization and the

data comes from bots, then you're making decisions

based on bots, not customers. Some kind of Ground

truth

on your online data—checking anything from the

Internet against a trustworthy data source—is

needed.

This is especially true for connecting ad and social data to sales. Attribution models are subject to gaming, but the Criteo/SteelHouse lawsuits were dropped, so instead of waiting for the techniques to come out in discovery we're going to have to dig some more to see how the fraud hackers are doing it. Happy new year.

In the news:

many advertisers say they don't know where their online ads appear https://t.co/6U1PcSYJwI via @WSJ

— Jack Marshall (@JackMarshall) December 5, 2016

Want to get a little more info on the brand-unsafe ad problem? Two minutes, easy experiment.

Get a fresh browser, not one you normally use. If you're on Safari or Chrome, try this in Firefox, or vice versa. (Don't pick a browser such as Brave that has a built-in ad blocker. This is about the ads.)

Go to your favorite—or least favorite—jihadi, white nationalist, or shitlord site.

Look at the ads.

That's the kind of thing I get based on the above site's ability to get ads based on its content. Crappy ads from advertisers that will settle for any impression, anywhere, whether brand-safe or not.

I don't see any reputable brands showing up when I do this with a fresh browser. How about you? LMK on Twitter which seems to be the place to talk about this stuff.

So why is the Sleeping Giants campaign even a thing? Why are people finding real brand ads on brand-unsafe sites?

The problem is that browsers have old bugs, some left over from the 1990s browser wars, that let information leak from one site to another. "Your ad on a site we know is crap" is pretty much worthless to an ad agency, but they will pay for "your ad to a known user" and pretend the brand safety issues don't exist.

But putting brand safety last, and trying to hack around it when people complain, can't work when the other side just has better hackers.

Here's the most facepalm-worthy but also totally accurate 2017 web advertising prediction so far:

Ad tech’s big marketing pitch in 2016 was offering “fraud free” guarantees. In 2017, it’s going to be “fake news free” guarantees.

— Lara O'Reilly (@larakiara) December 5, 2016

Really? A brand-new service rushed out the door, by companies that never cared about shitlords before, is going to have a chance? When shitlords consistently have better skills, and out-hack the entire Lumascape, without even mussing their "dapper" outfits? Good luck with that.

Maybe there's a better way. Brands, legit sites, and users can stop playing a losing game, and it starts with a few lines of JavaScript.

Bonus link: Without these ads, there wouldn't be money in fake news

As Professor Harry G. Frankfurt once wrote,

One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit.

Bob Hoffman points out that this is especially true in keynote speeches about online advertising. But all that bullshit is there for a reason. What would happen if you took the bogus scientification and marketing-speak out of the Thought Leader Insights? You'd get something more like these.

You don't need to make creative advertising because a machine, or some random person on Amazon Mechanical Turk, can generate a bunch of ads until something sticks.

Third-party tracking lets you reach high-value users for less money on low-value sites, because CTOs and minivan buyers regularly visit che3p-viagra.biz and watch the videos all the way through.

Fraud isn't a problem because code monkeys in an open-plan monkey house, reporting to douchebags and working for point squat percent of a company in four years, are smart enough to out-hack a fraud developer who is working on his own time, for 100% of the gain, in 30 days.

If you just educate users about how web ads work, they'll be happy to let sites they've never heard of excrete untested combinations of code onto the computers and devices where they keep stuff they care about.

None of those will fly in their bare form, but load them up with a bunch of "customer journey" and "deep learning" and now you've got a keynote.

So there may be perfectly good reasons why you might want to apply a substantial layer of bullshit to what you're doing. If so, carry on.

But what if you have a real problem?

The web is still a terrible place to build brands.

Web advertising is still low-value enough that it won't sustain high-reputation publications when print revenue goes away.

Third-party crap is still a security risk.

Then you need an alternative to bullshit, so go read more about getting Bob to speak at your event.

Here's a TV commercial from 1971.

Aww.

But here on the Internet, at least a lot of the time,

people are more like, I'd like to buy my tribe

a Coke® and the rest of the world can go die in

a fire.

People have an us-and-them side and a more inclusive side. And advertising has an unwritten rule about which side of the customer you're allowed to talk to. For a long time brands have stuck with a kind of generic globalism, not enough to satisfy a bona fide social justice warrior but never tied up with a specific tribe. Right-wing talk radio in the USA has trouble keeping mainstream advertisers. In one case, a blogger going by "Spocko" made fair use recordings of some radio shows and raised a stink to the advertisers. Despite some legal threats, it basically worked. Most brands are risk-averse enough to stay off talk radio. Even on the web, it's news when a brand shows up sponsoring a beheading video on a jihadi site.

Do things work differently, though, when it's an algorithm placing the ad in a niche that only sympathizers can see?

Timothy B. Lee writes,

The increasing polarization of news through social media allows liberals and conservatives to live in different versions of reality. And that’s making it harder and harder for our democratic system to function.

From BuzzFeed, Hyperpartisan Facebook Pages Are Publishing False And Misleading Information At An Alarming Rate.

The rapid growth of these pages combines with BuzzFeed News’ findings to suggest a troubling conclusion: The best way to attract and grow an audience for political content on the world’s biggest social network is to eschew factual reporting and instead play to partisan biases using false or misleading information that simply tells people what they want to hear. This approach has precursors in partisan print and television media, but has gained a new scale of distribution on Facebook.

Filter bubbling has been a thing for political advertising for quite a while, as Zeynep Tufekci pointed out back in 2012. Campaigns can target ethnic groups on Facebook with "voter suppression", or share misleading messages where they're harder for outsiders to track down.

What happens after the election, when tribal rage bubbles keep right on being a thing, but the political ads dry up? Are regular brand ads going to get placed on fake news, scenes of violence or threats of violence, and all the other us-versus-them crap out there? You probably wouldn't put your brand on Stormfront, but will you put your brand on one of the thousands of algorithmically micromanaged mini-Stormfronts of Facebook? Are dark posts the thing now?

This isn't a question about whose politics match with

whose,

or whether or not Facebook enables

targeting using data that we would prefer to keep

private,

or whether or not individuals should leave

Facebook.

The question is whether brands are now getting comfortable

with working inside bubbles that would

not have previously been considered brand-safe.

People keep saying that Google doesn't get

social

, but in a way, that's a compliment.

A lot of the time, people's idea of being social

is to split up into tribes and fling Internet poo,

or worse, at each other. Part of getting

social is developing the ability to exploit

people's other-tribe-hating brain circuitry in the

same way that spammers took advantage of open SMTP

relays

and SilverPush took advantage of

an opportunity to sneakily connect mobile user

data.

(The Peter Thiel

brouhaha

is raising the profile of the social

filter bubble issue by putting a human face

on it. Every time Sanford Wallace's smug face

made the news in the 1990s, it motivated us to

fix up our mail servers and set up the early spam

filters. Now it's Thiel in the news, making money

on both ends of the pipeline—recruiting 4GW

participants

on Facebook, and selling Palantir

contracts to track them down later. Ingenious

patriotism

at scale. So what to invent now?)

What's great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drinks Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too. A Coke is a Coke and no amount of money can get you a better Coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.

That was then. But today we're not even drinking the same damn Coke. I'm drinking the version bottled in Mexico. Meanwhile, out in High Fructose Corn Syrup land, they're drinking the other kind.

And that's just Coke. Are economic inequality and social distances between tribes getting big enough that the idea of a brand-safe ad placement is over? Are brands just supposed to take sides now? That's fine for fast food and soda pop, but what happens when an IT brand that benefits from economies of scale has to pick a side?

Related: Zeynep Tufekci on "Digital Inclusion and Decentralization"

Bonus links

Facebook is harming our democracy, and Mark Zuckerberg needs to do something about it by Timothy B. Lee (6 Nov 2016)